The Making of an Exhibition

September 12, 2025 | Treasure tales and archive snippets | 7 minute read

Approximately three years ago, I was having breakfast in Amsterdam with my long-time friend and colleague, Ariane van Suchtelen, curator at the Mauritshuis in The Hague (fig. 1)—an institution renowned for its exceptional collection of 17th-century Dutch painting, including masterpieces such as Girl with a Pearl Earring by Johannes Vermeer.

Fig. 1 Mauritshuis, The Hague

Our conversation turned to recent exhibitions Ariane had curated, many of which had featured paintings from collections in the United Kingdom. In the course of our discussion, I mentioned Holkham Hall and its outstanding holdings of Old Master paintings, antiquities, and an exceptional library.

Ariane noted that the Dutch works she had previously exhibited—primarily drawn from the Royal Collection and the National Trust—were already familiar to local audiences. What might truly engage and surprise visitors, she suggested, would be an exhibition showcasing masterpieces from private English collections, particularly those shaped by the Grand Tour. These works, seldom seen beyond the UK, could offer Dutch audiences a fresh and unexpected perspective, distinct from the more commonly encountered local artists.

We began to reflect on the unique character of English country houses within a European context. These estates often preserve historical collections in situ, and many remain inhabited by descendants of the original collectors. This remarkable continuity provides an exceptional lens through which to examine the history of collecting and could serve as the conceptual foundation for a compelling exhibition.

As it happened, the Mauritshuis had an unexpected opening in its exhibition calendar. A previously planned collaboration with an American institution had been cancelled, freeing the period from September 2025 to January 2026. Given that major museums typically schedule exhibitions three to five years in advance, this presented a rare and timely opportunity. That morning, the idea began to take shape: to develop an exhibition on the Grand Tour, featuring works from the Treasure Houses of England.

With the dates now secured, we had just over two years to conceptualize and realize the exhibition. And we did.

The Exhibition

The Grand Tour: Destination Italy opens at the Mauritshuis on 18 September 2025. It marks a significant milestone in the history of the Holkham collection, as it is the first time that an exhibition outside the United Kingdom will present a cohesive narrative of its holdings—ranging from manuscripts and printed books to paintings, sculptures, and works on paper—within the broader framework of the Grand Tour.

By the early 18th century, the Grand Tour had become a cultural rite of passage for the British aristocracy, typically centred on Italy. This journey was intended as an education in art, history, and antiquity. The quintessential Grand Tourist sought to return home with a portrait, a veduta (view painting), and either an ancient sculpture or a plaster cast—tangible tokens of their intellectual and aesthetic cultivation.

With this context in mind, we began identifying which of the Treasure Houses of England possessed collections most deeply shaped by the Grand Tour. Holkham Hall was our natural starting point, soon followed by Burghley House, whose collections owe much to John Cecil, 5th Earl of Exeter, who embarked on a Grand Tour as early as 1648. A century later, the 9th Earl would continue this legacy, significantly enriching the family collection. Woburn Abbey also emerged as a compelling candidate, particularly for its exceptional series of Venetian views by Canaletto, commissioned in the 1730s by the 4th Duke of Bedford.

Once the core collections were identified, we conducted an extensive review of catalogues and online resources to compile a focused list of objects for potential inclusion. For each house, we aimed to articulate a distinct narrative that highlighted the collection’s unique character. The selection process was challenging—given spatial constraints, we could include only 8 to 10 works from each estate.

We subsequently engaged in discussions with the owners, followed by on-site visits. Our initial wish lists were revised through dialogue and negotiation, resulting in a carefully curated final selection. Gradually, the individual stories of each house began to coalesce into a unified narrative centred on the Grand Tour.

At Holkham, three generations of the Coke family undertook Grand Tours. Thomas Coke, the principal founder of the collection, travelled in the early 18th century and acquired most of the works still housed at Holkham today. His son, Edward Coke, continued the tradition in 1738, spending significant time in Italy and sitting for a portrait by Rosalba Carriera in Venice—one of the exhibition’s highlights (fig.2). Nearly three decades later, Thomas William Coke, great-nephew of Thomas, also embarked on the Tour, and was portrayed by Pompeo Batoni, the pre-eminent portraitist of Grand Tour travellers.

Fig. 2 Rosalba Carriera Portrait of Viscount Coke, 1739 Pastel on paper, 50.8 x 43,2 cm

What distinguishes Holkham from other country houses—even those with similarly remarkable collections—is the profound interdependence of the house and its collection. The collection not only defines the character of the estate but is itself a testament to the legacy of the Coke family, particularly Thomas and Thomas William. Holkham remains an extraordinary time capsule of the British Grand Tour tradition.

Our section of the exhibition focuses on narrating the journeys of these two men—particularly Thomas Coke. We selected three portraits by artists associated with the Grand Tour: two by Rosalba Carriera in Venice (fig. 3) and one by Pompeo Batoni in Rome (fig 4).

- Fig. 3 Rosalba Carriera Miniature Portrait of Thomas Coke Oval, on ivory, 7.93 x 6.3 cm

- Fig. 4 Pompeo Batoni Portrait of Thomas William Coke (1752-1842), first Earl of Leicester of the second creation Oil on canvas, 248.8 x 60.2 cm Signed and dated P.Batoni pinxit Romae an 1774

To represent Coke’s intellectual pursuits, we included a manuscript and an early printed volume from his remarkable library (figs 5 and 6). A marble head of Roma (fig 7) illustrates his interest in antiquities, while three paintings—by Vanvitelli, Claude Lorrain, and Giuseppe Garzi (figs. 8-10)—illuminate his artistic sensibilities and collecting habits.

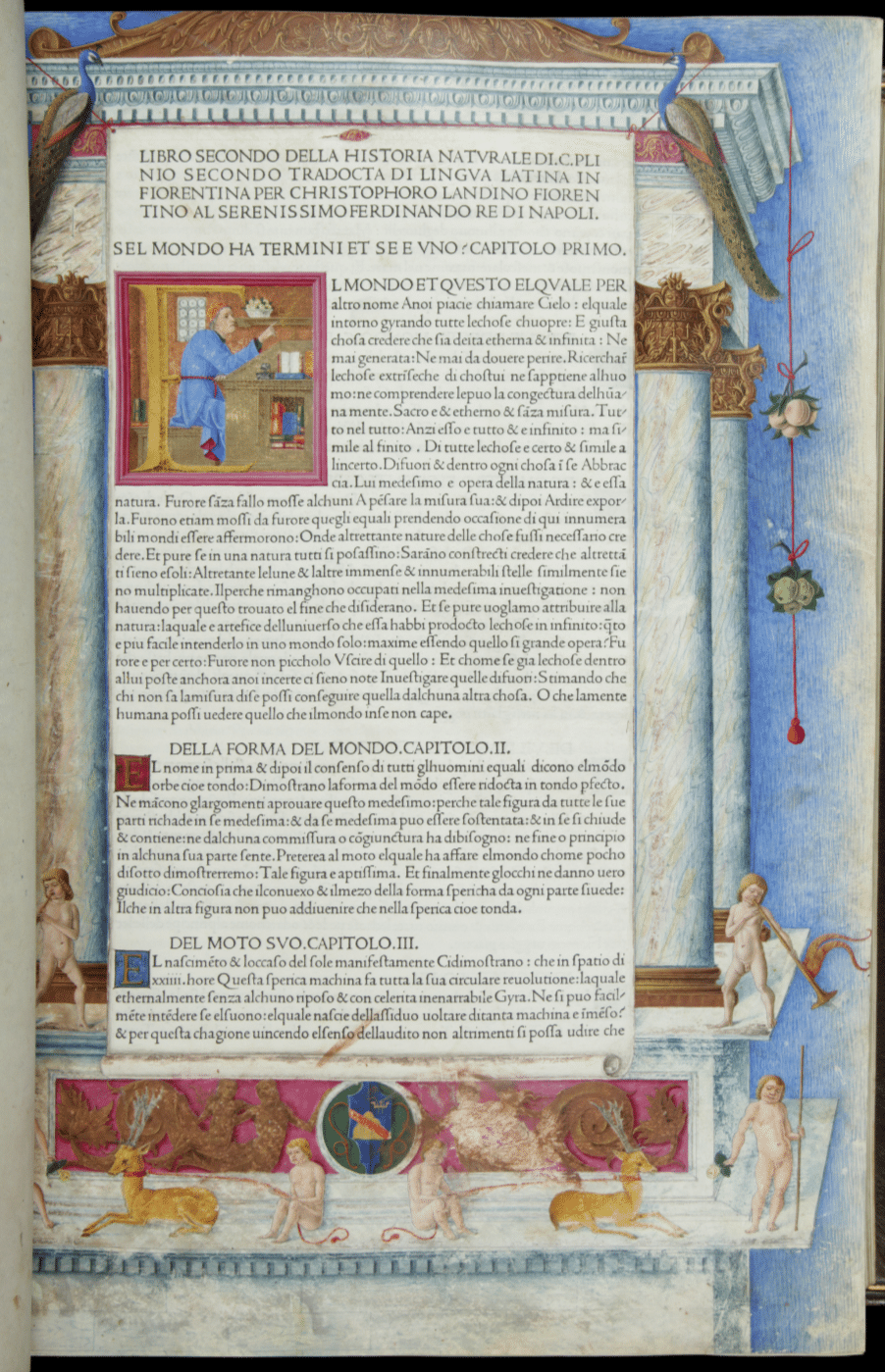

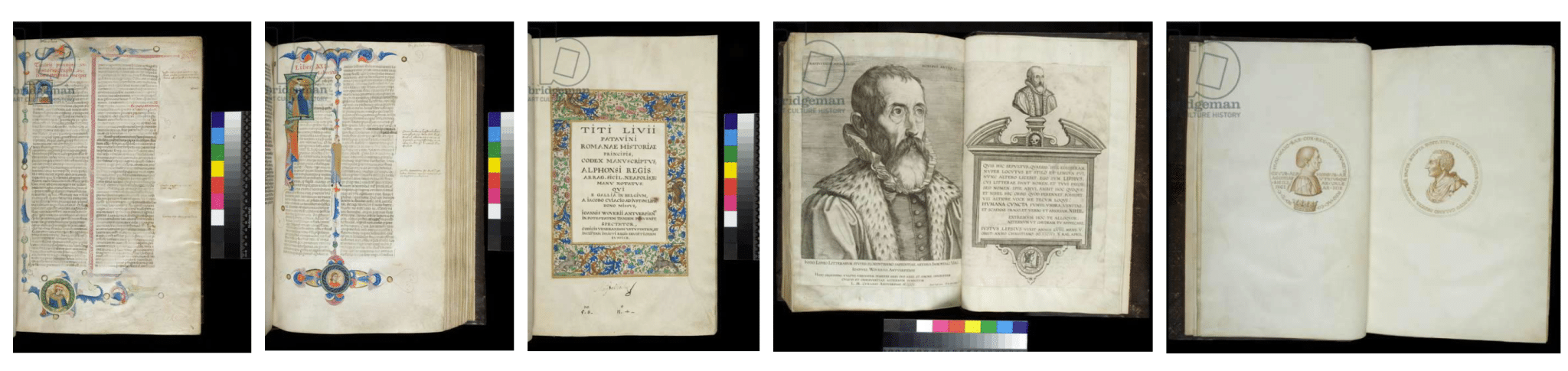

Fig. 5 MS. Holkham 351.2 Livy, History of Rome, Third Decade (Books xxi-xxx) Florence, 1460-1470 Binding Dimensions: mm. 339 x 237 x 47 Manuscript on parchment, with manuscript tempera illuminated frontispiece and book initials

- Fig. 6 BN. Holkham 1985 Title: Pliny, Natural History, in Italian translation Venice, Jean Jenson, 1476 Binding Dimensions: mm. 420 x 300 x 105 Printed book on parchment, with manuscript tempera illuminated frontispiece and book initials

- Fig. 7 Head of Roma Roman, mounted on a later bust of rosso antico Marble, H: 74,3 cm

- Fig. 8 Claude Lorrain View of a seaport and an amphitheatre, traditionally identified at Pola (Pula) with an artist sketching on the left, sheep and goats among ruins, galleys in the harbour Oil on canvas, 73.6 x 97.15 cm

- Fig. 9 Gaspar van Wittel View of Saint Peter’ square, Rome, 1716 Oil on Canvas, 54.6 x 114.3 cm

- Fig. 10 Luigi Garzi Cincinnatus at the Plough, 1716 Oil on canvas, 21.92 x 182.88 cm

With the object list finalised, we turned to our contribution to the exhibition catalogue. This became a collaborative scholarly effort. Laura Nuvoloni, librarian at Holkham, authored an essay on the formation of the library. Lucy Purvis, the estate archivist, contributed an entry on Thomas Coke’s account book—which details his purchases during the Grand Tour—and a study of the bust of Roma. I personally focused on the art collections and prepared the catalogue entries for the paintings.

In the final phase of the project, we assessed the condition of each object, arranged for specialized art transport, confirmed the installation plans, and completed the loan agreements. Laura will travel to The Hague to supervise the installation—becoming the first among us to witness the exhibition’s realization.

We hope that The Grand Tour: Destination Italy will offer visitors the same sense of discovery and intellectual enrichment that inspired us throughout the curatorial process.

Maria De Peverelli

Back to Journal Back to Journal