An Arrival of Cranes

May 2, 2018 | Learning | 6 minute read

The Crane is instantly recognisable, not only is it huge but unlike a Grey Heron it flies with its neck outstretched

As March turned to April this year, we all experienced a sense of relief. After the cold winter weather in late February and early March, the so called ‘Beast from the East’, the idea of a nice warm spring was a welcome thought. That however was not quite how it played out. Early April remained cold and only a brief respite came mid-month when warm winds from the south brought us a short yet most welcome hot weekend. Prior to that, the appearance of spring migrant birds had been slow in appearing whilst our breeding birds for the most showed much reluctance in beginning their nesting activities. Lapwings seemed low in number (all along the coast not just here) it is thought due to the hit they took in the cold late winter weather and those that were here delayed nesting by at least a couple of weeks. We did have one pleasing development that really made April stand out this year; the appearance of several Cranes.

Cranes are large stately birds. With their long necks and legs they could be described as looking rather heron like. They can however stand up to 2.2 metres tall which makes them over twice the height of a Grey Heron! Cranes are birds of wild places. They need space with little disturbance and are most common in northern Europe where they nest typically in bogs and marshes before migrating south to southern Europe and north Africa for the winter. Cranes are very much opportunistic omnivores having a diet that takes in root tubers and invertebrates whilst in Spain where large numbers often winter, cork oak acorns are favoured.

Small parties of Cranes fly over Holkham each spring on warm days

In Britain the Crane is a bona fide rarity; in 2016 48 pairs bred, a record number but still hardly a significant population. This however was deemed a huge success and a milestone as the Crane had undergone a very chequered past. At the moment there is indeed much to triumph as habitat restoration and a reintroduction project in Somerset are all playing a part in creating a brighter future for a species that for many years had actually disappeared completely from the UK. Up until 1981 it was thought that the Crane had not bred in Britain since the 17th century.

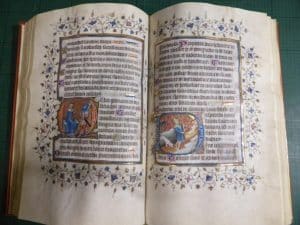

Prior to that Cranes had been plentiful enough in the wild open wetlands of the Fens and the Broads to be hunted and served up with some regularity at medieval feasts. It has often been quoted that for Christmas dinner in 1251, King Henry III and his court ate some 115 Cranes. Amidst the background of hunting, as time moved on many marshes and great swathes of Fenland were drained thus depriving the Crane of a homeland and it was little wonder that extinction occurred.

Cranes continued to appear as lost migrants but it took until the 1980s before the first nest was again recorded. Even this plays a major part in the story of the Crane’s recolonising of Britain. The nesting area was in a great area of private marshland at Horsey Estate in the Norfolk Broads. Here they had the solitude and habitat to remain and slowly but surely their nesting attempts became more frequent and successful. By the time of the record breaking year of 2016 some 11 pairs were nesting in the Broads alone.

Protection and lack of disturbance in a wide tract of habitat was the key to their success. It is widely thought that the Crane’s growing population has also helped in other sites around the UK becoming colonised. We know that each spring wandering birds take to the skies on warm days and fly far and wide around East Anglia presumably on the look-out for other areas to colonise. It could therefore be that the new breeding sites in the Cambridgeshire Fens, Humberside and even Scotland were birds that originated from the Norfolk Broads.

This Crane was one of two that dropped into the marsh this April. Its large tail is known as a ‘bustle’ and almost like a human’s fingerprints it varies individually

This finally brings us around to Holkham. Unsurprisingly the Cranes are rare birds here although they are now quite regular in small numbers and each spring we now eagerly await their arrival. Any time between mid-March and late May a hot day with little wind can almost guarantee the odd Crane sighting in North Norfolk. Some may perhaps be lost continental migrants but as often the birds pass one way and then return the next or even on the same day it is certainly most likely that they are birds from the Broads.

Cranes have fantastic loud bugling calls and this is often the first clue as to their appearance. Squint into the sky and you might be lucky in seeing the distinctive profile of these large soaring birds circling or passing by. Usually they are so high they might appear just as a dot in the distance but if you are really fortunate they might drop lower or even land. Flocks of four and nine (a record number for us) passed through this April typically not landing but a week later a pair actually made landfall on one of our quieter spots.

It has long been an ambition of those working here to see Cranes perhaps prospect at Holkham but in reality our habitat probably does not quite fit the bill. Cranes really do like undisturbed water logged swamps something we ordinarily can’t quite offer. However where they landed was almost perfect following the winter’s rainfall, low lying fields of hard rush (or Juncus) looked to be the perfect spot if we were ever to attract Cranes. Our excitement was short lived as they had gone the next day but it at least proved that we could maybe in the future offer something for these most magnificent of birds.

Adjacent marshes to the reserve offer the best habitat for Cranes, an area of marshland dominated by rushes in semi permanant shallow fresh water

View all latest blog posts here.

Back to Journal Back to Journal